In that previous post I mentioned friction bearings. If you'd like to bear with me for some technical info, here's a little more detail on them.

This is a standard, present day roller bearing truck.

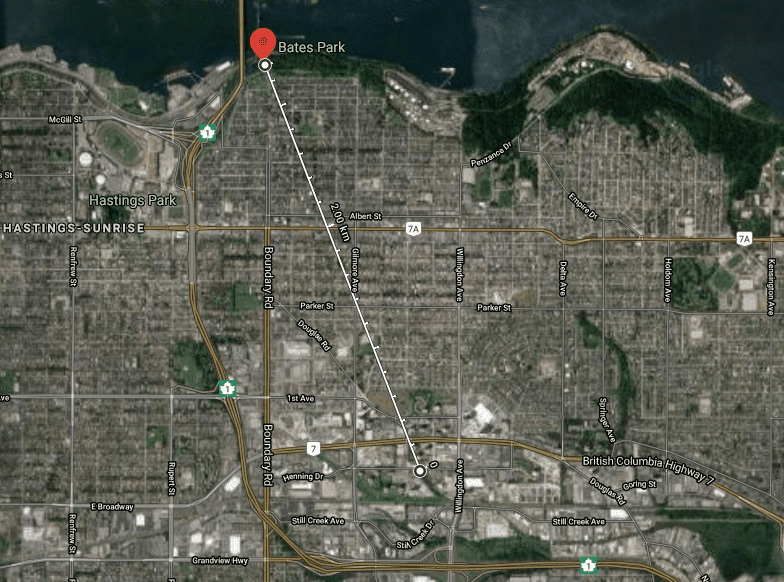

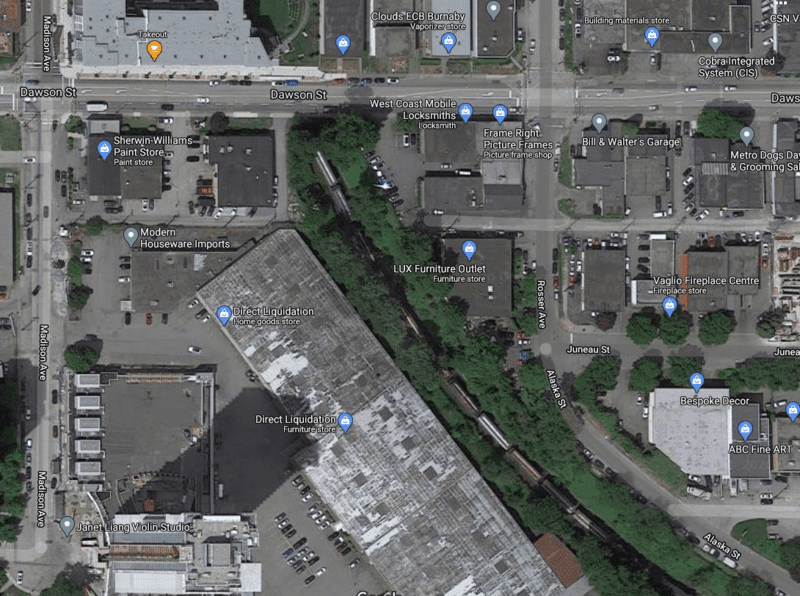

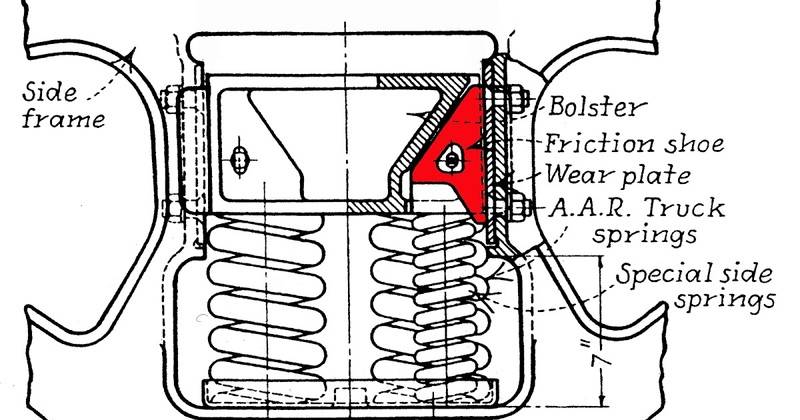

When I say "truck" I mean the assembly that includes the two wheelsets, two side frames (one showing on this side in the picture) and the center bolser that connects the two side frames. In this picture, the truck bolster is supported by the nest of coil springs and runs across to the side frame on the other side. The bolster slides up and down in cast guideways between it's end and the side frame, and it won't come out of the side in this configuration. To do so, you'd have to first jack up the center to take the weight off the springs, then remove the springs to allow the bolster to drop low enough to disengage the guides. You wouldn't do this on the car, only if the whole truck was removed first. A crude form of shock absorber is included in this design; a cast steel wedge slides up and down, using it's own spring to hold it in place to create friction to limit vertical movement. These are called stabilizer wedges, shown in red below. They're a wear item and are regularly changed out when a visible wear limit line is worn off.

The difference between the first picture and a friction bearing truck are quite complex. As you can see in the roller bearing version, simply lifting the car and truck will usually allow the wheel-set to drop out, remaining on the ground and therefore making it quite easy to change worn or defective wheels. When brand new, there is a 'frame key' riveted in place to keep the roller bearing from dropping out, but in service it's quite common to not bother putting them back in after changing a wheel, letting gravity keep the car on the wheels. In practice, this is pretty reliable. There's the other way, instead of lifting the car you position it over a drop pit and lower the offending wheel, putting up a new replacement. This is me at work dropping an old wheel... (note the dazzle camouflage war paint on the box car)

Now friction bearing axles on the other hand are both an extremely simple design yet much more difficult to dis-assemble for servicing. The outside difference is obvious; there is no roller bearing end cap, instead you see a hinged cover. (This shows 5 1/2 X 10, which is the bearing size. Such a small bearing, 5.5 inches in diameter and 10 inches long, even in roller bearing configuration is no longer used as it didn't carry much weight. The old wooden box cars didn't demand as much).

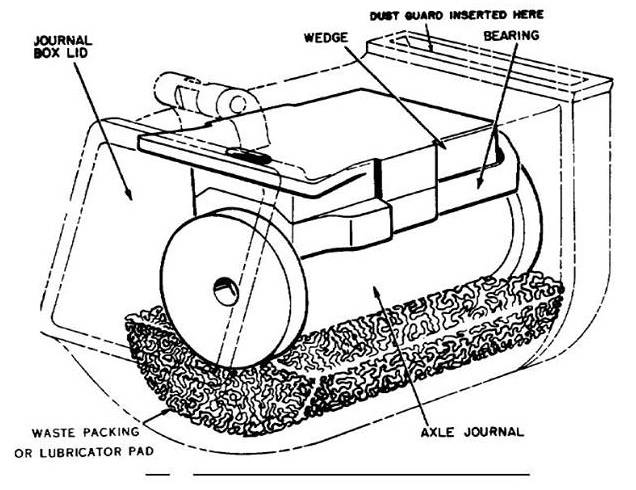

Inside when you pull up the lid, you see this. The terms for this is a 'journal box'. The round end is the flanged end of the bearing, while the brassy block on top of it is, well it is brass with a babbit shell. On top of that is a steel wedge to spread the load between the brass and the top of the truck box while under the bearing you see a dark fuzzy area that's actually a pad soaked in the oil that is pooled in the bottom of the box, continually wiping and oiling the bottom of the bearing as it rotates.

To make it clearer, here's a drawing. During a train inspection, a car inspector would be equipped with a variety of tools; various gauges to check wheel dimensions, plus a pull hook to open the spring-loaded lids. Often a 'shoeing bar', a pry bar about 36" long would be carried as well to change out brake shoes. In addition, a jug of oil would be used to top up any boxes that required it. Often, the crew would work in teams so that one person would do the oiling while another changed shoes, so you didn't have to carry everything at once.

Anyway, the diagram does show how simple the design is. The concept was in use from the beginning of railroading until they were phased out in the end of the 1980's after Timken pioneered the roller bearing concept in 1956. They were finally prohibited at interchange on Jan. 1 1994.

But while the design is simple, the maintenance for it was not. Besides the need to check oil every few hundred miles, the bearings needed to be pulled and inspected every couple of years, and the lubricator pad changed out. This part wasn't so bad as simply jacking up the center bolster would allow the truck to lift up and the wedge and bearing could be pulled out. And those were heavy bearings, you learned not to let them crush your fingers after the first time!

Changing out a wheel however was where things got difficult. Instead of merely dropping out of the bottom of the truck like roller bearings, the plain bearings are completely enclosed which means dismantling is needed. With the car jacked up and the whole truck rolled out, an overhead gantry with at least three separate sets of chain winches would be hooked up - one for each truck and one for the center bolster. First, the weight was lifted from a truck side so that the wedge and bearing could be removed. Then the truck side is lowered to allow the pad to be pulled out of the bottom. There was usually a heavy loop sewn to the front of it so a hook could pull it out. Then the truck would be raised up just enough to let it move laterally away from the bolster until it cleared the bearings. Repeat for the other side. Putting things back together was pretty much the same but in reverse; with a couple other things as well. Where the diagram says "DUST GUARD INSERTED HERE", a dust guard was a simple felt strip, coated with something like roofing tar. The dust guard was actually laying on top of a rubber seal that worked similar to the seal on a crankshaft - it prevented unwanted loss of oil. Also, the bearing sizes were nominal but came in both standard and undersizes, so the journals had to be gauged to see what size bearings went back in. There was a simple go/no go sliding gauge and bearings came with red, white or yellow paint dots on them to let you know if they were undersized or not. It was permissible, but not recommended to let an oversized bearing go into use but not one that was smaller than gauged for obvious reasons. Also not shown here, some trucks had side bearings as well, preventing fore and aft movement of the axle when pressure was applied from brake shoe application.

Not only was this arduous work, it was generally extremely dirty as a couple of years of oil and road dust left a quarter inch of black crude everywhere you touched.

This is one of the portable lifting frames we used outside, here it's shown with a roller bearing but you can see how the lifting jacks can move laterally to allow the truck frames to separate. This version used manual hydraulic jacks while the larger ones inside the main shop had powered chain lifts.

This was one of our tools, a standard wheel gauge that checked for rim thickness, flange thickness and other problems. It also had a marked scale to measure things like flat spots from sliding wheels and 'shell outs', chunks of tread gone missing. There were specifications and limits for all sorts of things, including heat discoloration and cracks. Common in the old cast iron days, an inspector would use a hammer to tap the wheels to listen to the ring and if there was a crack, it would sound flat. Newer cast steel wheels rarely had this problem.

Not all wheels removed from service were scrapped, some that were thick enough were simply put on a lathe and turned back to the proper profile. This wheel lathe in our shop renewed quite a few wheels per shift. As well, bearings were renewed during this process.